By around 5:00pm, Peter and I had made our way to Tomato Rock via an overgrown mining road that used to end at a nearby (now closed) quarry. My feet feel as if I’ve been walking on glass for the last 13 hours. My hands, filleted.

Tomato is a squat, nine-foot boulder with a few-move problem on it that’s too easy to even register on the modern V-Scale. In the past, I’ve done the much harder sit-start variation. I’ve done this problem without hands.

But this evening, I couldn’t fathom how to get up to it’s lowly summit by any means. The soles of my shoes skated off the high feet like ice; the mono finger pocket felt far too painful to hold my weight, let alone use to dynamically launch from to pinch the next hold. I sighed, looked at Peter, and shrugged.

“Maybe, I’ll save this one for tomorrow?”

We were thirteen hours, and twenty-seven routes into the fifty-three Flatiron Classics linkup. The “Classics” designation made by guidebook author Gerry Roach from his venerable Flatirons book. Seems most anyone that wanders among the hills west of Boulder has a copy.

I bought my own copy when I still lived in Denver, almost seven years ago. Back then, I would have to get up early to catch the bus to Boulder. I’d wander the trails and soon enough: scramble up the red sandstone formations found around what must be the most radical city parks in the country: Boulder’s Open Space Mountain Parks. I would take the trip so many times – sometimes multiple times a week, the woman I was living with was certain I was cheating on her. I’d have to check in periodically and give her my location. That relationship fizzled, I moved to Boulder, and the Flatirons took hold.

Early in the morning, well before Tomato Rock, Peter led the charge from the parking lot at Chautauqua to our first area, The Amphitheater. Inside this natural citadel were our first four Classics of the day. Peter having a background as a scientist, had worked out the most efficient way for us to climb all these Classics – indeed: he had done the same treatment for over four dozen routes. Talking in a fast clip, he outlined our plan of attack in a jargon almost all our own:

“We’ll climb T-Zero, then move over to the South Face of the Second Pinnacle. Drop your gear there – oh! except bring the rope. Set up the toprope for The Slot, climb it, then rap down. While you do that, I’ll climb up the Southeast Face of the First Pinnacle, downclimb off the back, and get to The Slot that way. Once you’re done with The Slot, do all the things I just did, then retrieve rope. Meet you at the trail junction in Gregory Canyon!”

The trail junction was one part documented, defined trail, and another part unofficial social trail you wouldn’t be able to even see – let alone in the dark, unless you were intimately familiar with the secrets of the park. To even attempt this project, one would have to be. What we were doing would make no sense to a casual hiker, and made enough sense to real climbers as to seem comically absurd. I mean: why climb so many easy climbs in a row, when you could spend all your time climbing something hard, or high, or epic?! But for Peter and I, the game was endurance.

For 5.5, T-Zero is a somewhat heady climb, as the crux is overhanging, even if the crux move itself is on a massive horn. Earlier in the week, I had to refresh my memory of all the climbs in The Amphitheater. I’m glad I had. Every climb and the clever way we planned to link them all together seemed absolutely cryptic on my rehearsal. I repeated the climbs multiple times, spending hours in the same few acres of area.

On this morning, I went through the climbs in order, feeling sluggish and uncoordinated – not ways I’d describe a competent climber. But with my familiarity, I could mumble through the routes without incident. I hoped though, that I would soon wake up fully. It was going to be a long day.

With The Amphitheater Classics done, we moved cross-country up a steep hill to the First Flatiron – an absolutely colossal formation that takes precedence over the landscape when seen from the trailhead. Again, Peter had a most extrinsic way to go – a route you’d only take to climb the most routes in the least amount of mileage. We scrambled up The Spy just to the north of the First itself, then attained the North Arete of the First Flatiron, dropped our packs, then downclimbed Baker’s Way. After pulling the 5.4 crux move in reverse to get off the First, we descended down the trail to the start of the East Face Direct route, and climbed back up to our packs, finishing the route at the summit of the formation.

Most of this was done in the dark; dawn was just breaking when we were on the last easy pitches towards the summit. The first light of sun exposed a low inversion taking place but we were well above the scattered fog that was enveloping Boulder. The city itself looked as of it was on fire, with smoke billowing from the neighborhoods and University. Sun pillars emanated out like spotlights. Climbing the First Flatiron can be a slightly nerve-racking experience: the first pitches on the direct route are to put simply: thin.

But Peter and I have climbed it so many times, we’ve memorized the location of each hold – if not named some of them. Grabbing the little nubbins and crystals on the rock used to ascend the rock was as comforting as grabbing a long-time romantic partner in bed to hold them even tighter.

Not all the Classics feel this way. I had the disadvantage for this project of not having climbed all them even once. To me, those other climbs held little pockets of anxiety to be explored. Even though the climbing should be easy, the guidebook grade could be sandbagged or fail to truly communicate the difficulty or seriousness of the climb. This particular guidebook has… let’s say: somewhat of a reputation for that.

With the First done, it was onto the Second Flatiron, and downclimbing Freeway. We’d be downclimbing routes often on this über-linkup, as it makes linking up disparate routes a lot faster. Flatiron routes can be longer than they are taller and the 538 feet of vertical measured on Freeway will take you 686 feet horizontally away from your starting point. The downclimbing, however awkward looking to a passerby, felt natural this early in our romp – I’m also probably the only person stupid enough to have downclimbed this route twenty times in a day – a different story, altogether – but mentioned to highlight just how obscure our rock obsessions are.

Down Freeway, then up Dodge Block, moving then to climb Chase the Sun on the Sunset Flatironette behind the Second. Then, off to the Third Flatiron and its satellites. We were on a tear. Mildly.

Another complicated linkup (try to keep things straight – I needed to draw a picture when Peter first described it to me): up the Standard East Face, smoking past a line of climbers roping up. Rapping off the side to the last belay station, where we then set up the top rope for Friday’s Folly, a climb we both sent in approach shoes. Being one of the harder and steeper climbs, I’ve taken whole afternoons to set up a top rope soloing system to rehearse this one, 80 foot pitch. I’ve actually never have climbed it on lead, but feel in a weird way, I could probably solo it just fine on a good day.

Thrashing down the Third’s south gully past healthy groves of poison ivy, we approached W.C. Fields Pinnacle from the west. Both soloing the 5.4 West Face (bonus route!), we then set up a top rope at its summit anchors for later. Rapping down the east face part way off our 30 meter rope, we then carefully downclimbed the remaining 30 meters that our rope was too short to cover (no problem!), and made our way to the start of the East Face of Queen Anne’s Head, a 5.5 climb I’ve never done before. Halfway up, I broke a foot hold – an interesting and exciting sensation. Gotta stay focused.

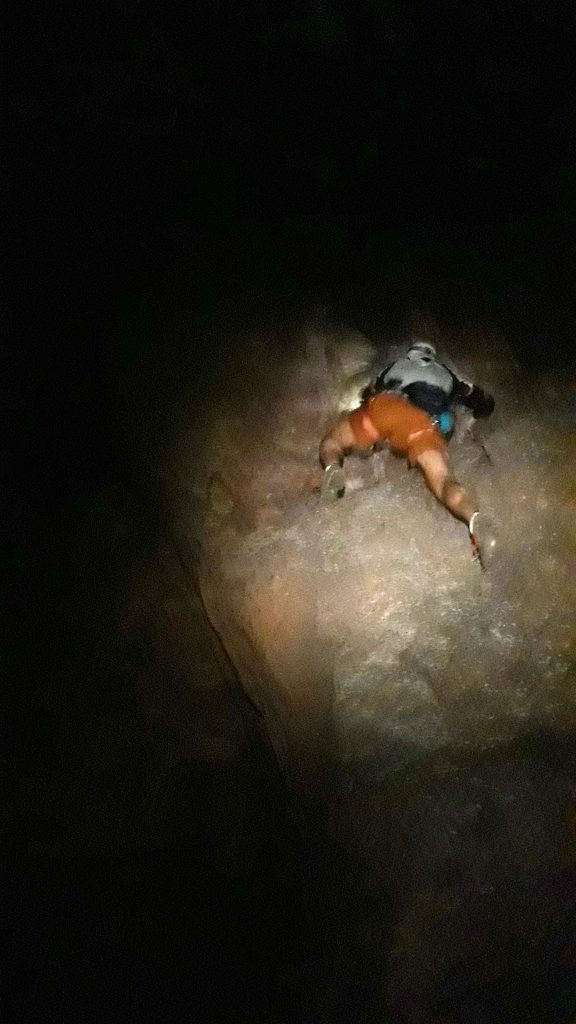

Peter had figured out yet another improbable way off this formation: rap to the northwest, climb down into The Ghetto (a semi-hidden bouldering area that can only be accessed itself by a 5.5 route), then climb out of The Ghetto via a different route to get back into the south gully of the Third. Then, descend all the way to the toe of the Third to do East Face, South Side.

We climbed South Side, ostensibly passing parties we first saw on our first route up the Third (we: moving so fast, and they: moving so, so slow) until the Dogs Head Cutoff pinnacle, which we rappelled off from an awkward and questionably slung rock utilizing a single piece of webbing.

I was caught in a Catch 22: I couldn’t get in a good position to rap without taking both my hands off the rope, but doing so made it dangerous to even be set up on rappel. I’ve practiced just soloing the traverse pitch off, but with so much climbing, Peter and I agree that if you could avoid climbing that wasn’t on the list of things to do, it’s better to do so; it saves the wear and twear on your skin, feet – and your endocrine system.

Peter opted to downclimb the monster jug-riddled overhanging Winky Woo, but I, having never done that, opted to climb it from its base, earning me two bonus downclimbs of the Southwest Chimney Route (so much for avoiding unnecessary climbing). Winky Woo is one of the steepest routes on the list – a route whose cruxes feel natural for anyone who warms up on gym V0’s set on an overhanging bouldering wall. The Woo is just like those warmups – except you’re 100 feet off the deck.

I ran down that damn south gully for the second time, doing a terrible job again of avoiding the devil’s weed, to the base of W.C. Fields and belayed myself up its steep, 5.8 west face route back to the summit to meet Peter, who then informed me our rappel off the west face also didn’t reach the ground, so I should be careful to not rap off the ends of the rope – and be prepared for some tricky, overhanging downclimbing.

“But it’s short,” he added.

Once done, and for the third time, we descended the south gully, this time to hike for a short time on the Royal Arch trail. Having been hidden in a jungle of poison ivy climbing rarely visited rocks, it was quite the shock to be engulfed by day hikers. Our lightweight harnesses jangled with belay devices and caribiners (and no climbing protection – too heavy!); their backpacks letting out distorted music from bluetooth speakers.

But soon we were off trail again – having zagged when the official trail zigged, making our way up to The Thing aka The Morning After aka The Needle’s Eye. The first pitch has a 5.7 roof I’ve never pulled off successfully solo, but after asking Peter for a belay off his skinny, nearly psychological-in-safety 7mm static line, we summited easily. Off down again to downclimb Yodeling Moves – a giant hidden arch, which itself took us down to the base of the Fourth.

More route shenanigans took place: after having climbed the two first pieces of the Fourth Flatiron, we exited to climb Challenger, then Takin’ Care of Business – an incredible chimney that looks like an creme-filled cookie standing on one of its end but with the creme removed. Rapping off the summit, we then finished the third piece of the Fourth, descended down the social trail to the start of the East Face, North Side route on the Fifth Flatiron. I’m shaky on this route, so I opted to put climbing shoes on, even though I knew multiple pitches climbed fast would most likely be terrifically painful for me.

And they were.

At the summit, as Peter elected to downclimb the East Face, South Side route, I elected to climb up and meet him in the middle. We reconvened again at the base of the route, and made our way south to Hillbilly Rock’s East Side, which we scramble up quickly, then climbing down the North Face route.

Incredulously, or route count was up to twenty-six! Meaning we only had two routes left to finish for the day. The next route was a downclimb of Stairway to Heaven, which would take more than 40 minutes, as the route was 1,000 feet long . My feet tender, and hands: raw, but there was no way I was going to hike down to the base of this mother just to climb back up. So I followed Peter down, trying to keep his pace. For someone 20 years older than me, the dude can move.

I thought to myself,

“Less ice cream this Winter,” and sung to myself an obscure punk rock classic: Jim Carroll Band’s, People Who’ve Died, ad-libbing my own lyrics starring Peter and I falling off the routes we were climbing on today.

“Justin was following Peter down a steep red rock

but started slipping and falling – a crystal he was standing on popped

Peter tried to catch him with his outstretched hand

While Justin was screaming as loud as he can

But Peter missed him by a country mile

Justin wasn’t caught –he died!”

“That’s a pretty morbid song to be singing, given the circumstances!”, Peter reflected upon me.

We were still 500 feet from the bottom of the route. One inattentive slip…

Peter politely waited for me at the base of the climb in Skunk Canyon (he did a lot of waiting on this day), and we sauntered together towards Tomato.

And like Tomato’s profile, this circuitous report has come full circle. I eyed up the holds of Tomato’s diminutive south face, and decided to just go for it. Turned out, my feet actually weren’t made of ice and didn’t slip off when I applied pressure through them. One move later, I had summited the Big Red.

We can go home!

For the day. Tomorrow was another day altogether, with 17+ additional routes to summit. Mon Dieu! I go home and prepare the body: soak in epsom salts, apply moisturizing lotion liberally, clip all those damn toenails killing me in my TC Pros.

Waking up at 4:00 am, the body is not feeling exceptionally accommodating to my plans. From 4:10 to 4:30, I found myself bent over in pain, head in hand. Our first climb this day is the aptly named, Satans Slab, which features two pitches that are extremely thin and unprotectable. I have no names for the holds on this route as I do for the First. The “holds” are so small as to not have the levity to require their own names.

I text Peter, embarrassingly, that I’m out. I feel as if I cannot safely continue. It’s not a decision I made easily, but the body won’t perform what the mind is beseeching it to do. Peter seems understanding: “More time for me to sleep in!”. And that’s that.

The next day, which we had planned to use to finish up the project by climbing some of the hardest routes on the list: it rains. That saves face for me – we couldn’t have finished on day 3 even if I didn’t bail on day 2, but I’m left unsatisfied with my performance. The body heals quickly, and like many projects and challenges I’ve come up short for, I’m thirsty to try it again – to my fulfill honest intentions.

Peter texts me a few days later,

“Free this weekend? How are the feet? Wanna try day #2 for fun”

And of course, I’m game.