Pinned. In front of me, like plated back spikes of a malevolent dragon, was a sheer tower of rock twelve feet high, overhanging on all sides, 300-foot drops to the west and east, and no obvious way to climb up, over, then down to the next spire. How many more of these I would have to surmount was uncertain, but I’d already climbed over three of them. I told myself – perhaps in an attempt to keep calm, that it’s good I’m continuing to go forward, because there’s just no way I was going to be able to reverse the moves previous to get back down to the safer ground I left behind.

But now I was sitting on a small platform between these two spires, staring incredulously in front of me, not having any idea how to move forward. Perhaps if this spire in front of me was in the middle of a grassy field, it would make a sporty boulder problem, but my little platform was only about two feet square, and there was only one sloping hand hold I could reach and some slippery feet to work with if I used my imagination. I investigated a sneak to the east, but it just cliffed out. The area I was sitting on was so tight, I thought of maybe even stemming between the two spires, but it was just out of reach even for someone like me with equipped with long ape-like arms.

I felt, well: a little stupid – or at least inadequate. Other people had been able to get through this part of the route and no one talked about this super cruxy part. I just… didn’t have the cajones to go forward. That’s just all there was to it. What was I doing here at all?

I collected myself to begin the unenviable job of reversing the terrain. The climbing clocked in at maybe 5.7 – a loose alpine 5.7 for sure, but nothing world-class. But as I climbed back up the last pinnacle, I could hear my stove kit clatter around somewhere in my 40 liter pack. I was on the third day of this ridge traverse and had all the gear stuffed around that cook pot to prove it. I was becoming mentally fatigued and I worried my decision process was becoming deeply affected. I didn’t want to make a stupid decision because I was too tired or impatient to make an intelligent one, and I leaned heavily onto the built up talents of all those climbing sessions indoors over the Winter, and all those scrambling days outdoors afterwards – many at night, to see me through.

The first spire I had to backtrack featured little if anything for holds. The trick was to grab the absolute top of the tower, then utilize one of the sides to find some sort of purchase for your right hand and foot, pulling awkwardly with both, while smearing with your left foot. Lots of body tension. This forced much of your center of gravity over the right side of the spire, and out into some serious exposure.

Little by little, I crawled back over all the past spires, until the face climbing commenced. I had noticed a tunnel through a chockstone that seemed to allow easier passage on the other side, and I took a few minutes to mine out a bit of talus to make the hole a little larger – large enough to squeeze my body through. It was of no use: I could go through, but the pack couldn’t. It seemed too awkward, and if I flubbed it, several hundred feet of air was awaiting to greet me with the open arms to oblivion.

The face climbing now below me was chossier than I would have liked and I had kicked a few stones down while climbing up. The cruxes were a series of slabby traverses over some overhangs which thankfully themselves were solid, albeit almost featureless. “Trust your feet’ was my mantra. I got back down to near the plane wreckage that littered the bottom of the face of this unnamed peak, and assessed my situation.

I felt fustrated – a failure I guess. I felt I summited this small peak honestly, but couldn’t traverse over it – I’d have to make this peak an out-and-back, and use the much easier Class 4 sneak I had stumbled on earlier to simply go around the east side. I just couldn’t understand how everyone else before me had done it. I continued beating myself up over my lack of skill and confidence. I felt almost betrayed with such a sandbag – no one else had noted this peak in their own trip report. This seemed almost dangerous to other people challenging themselves on this terrain.

It was then I realized that the Class 4, grassy – happy looking, even sneak to the east was the actual way, and what I was mucking about was just yet another tower of many many dozens on the route and this one had fooled me into thinking it was the way. A major route-finding blunder. One just has to laugh a big gaffaw! at feeling that little icy finger of doom, only to realize the situation is more like a dream, where you come to work naked. I rub a little sleep out of my eyes, and breath a sigh of relief. How did I get here?

Three days prior, I somehow fandangled my housemate into driving me to the start this trip in RMNP – up Trail Ridge Road to Milner Pass. Sheepishly, I thanked her for the ride. But she insisted to me she wanted to go – and had a Parks Pass too, which meant we didn’t have to pay an additional entry fee to get in. I do love a good deal.

Project Vanishing Point

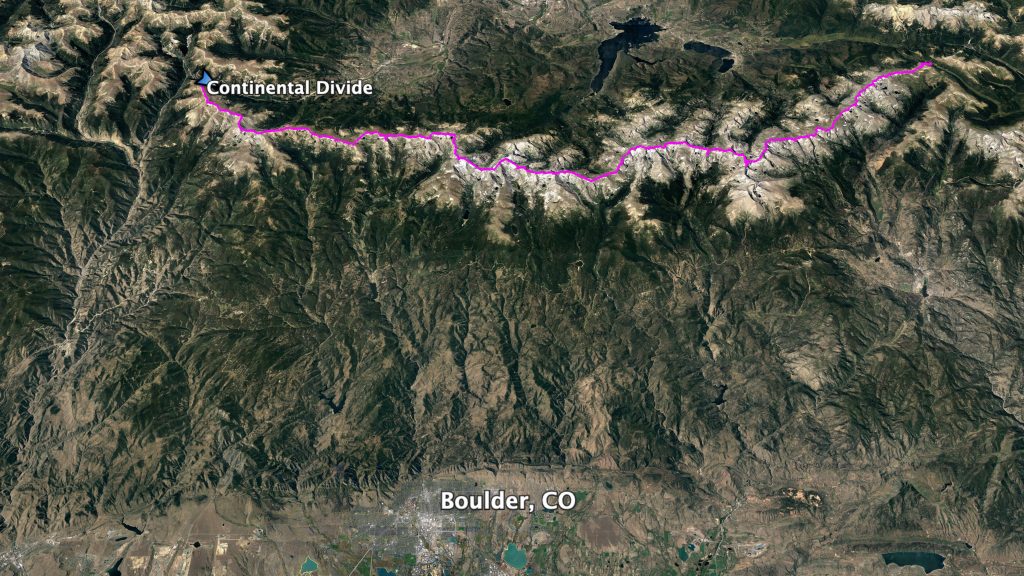

My goal for this project was to hike from Trail Ridge Road/Milner Pass south to the next paved road, Berthoud Pass – both passes being on the Continental Divide. I’d try to stay as close to right on the Divide as I could the whole way – the goal being to never drop into a basin below me. Fine if I did – storms do roll in and it’s not worth being stubborn if you’re faced with a dangerous situation like the weather one of those can bring in, but I’d have to climb back up to my starting point if I did and that’s just too much work for someone so lazy.

To make my goal work, I brought along a stove to melt the snow and ice that are found en-route, fed by the ancient glaciers found slumbering on the east side of the Divide throughout almost the entire length of the line. From paved road to paved road, it was about 45 miles as the crow flies, but because of the wandering nature of the ridge itself, it would be more like 75-80 miles traveled on foot.

I had sussed out the difficult parts of this route – and there are many, considerably all summer, taking bus and bike rides up to the trailheads just up the hill from Boulder, CO where I live, bivying near the trailhead in my secret spots, then waking up very early for marathon days romping in the mountains. The approach just to the Divide is sometimes around 9 miles, so these recon trips are commitments in themselves, and a great way to get fit.

I didn’t expect there was going to be much that would surprise me, except for a few miles where the ridge of the Divide skirts through the Boulder Watershed, just south of the Brainard Lake area. I felt it almost indecent to enter that area more than I would need to, so decided to stay away until the trip itself and get in and out as fast as I could. I knew there was some difficult terrain in there, but I felt that my recon trips for all the rest of the route would be good training for this part too.

In total, by staying on the Continental Divide, I’d be summiting around 50 named peaks, depending on how you counted. Some of these named peaks were more historical points, while others felt more like bonus peaks – near the Divide, but not quite on them.

To stop my trip from becoming, “Summit everything within sight”, I used the following guidelines: the peak has to be on the Divide itself, not simply near it, and it had to have at least 300′ of rise. Sometimes the very summit of a peak isn’t exactly on the Divide, but if the terrain keeps going up to the summit, you need to stand on the summit. Chiefs Head for example, will need to be summited, but Mt Audubon found just east of the Divide wouldn’t.

The peak also has to be ascended from the main ridgeline and coming from the north and going to the south, that usually meant the north ridge. Bypassing minor towers on the east or west side is fine – not every single high point had to be topped, but you have to follow the ridgeline itself. Pauite’s North Ridge is probably the biggest crux of the whole route, a full mile of Class 3/4/5 scrambling starting at the south ridge of Algonquin. It’s not to be underestimated. Many of the unnamed towers on the ridge are out of the question to summit, needing at the very least a rappel off to get down from the tower, and I wasn’t going to bring a rope. But, the last large ridge up to the summit of Pauite is one of the highlights of the entire line and is not to be missed.

These guidelines in place keeps the spirit that what you’re doing is not just a peak bagging exercise, but a ridge traverse. This isn’t Nolans.

One exception is that is the summit of Arikaree, deep in the Indian Peaks and right in the middle of the Boulder Watershed. There doesn’t seem to be any direct ridge route from Navajo to its summit – or none that I know if. A glacier actually splits its ridgeline in half and traversing over the subsidiary tower and then to the summit itself would involved rappeling down into an ice gully and somehow climbing back up. I do not believe it’s ever been done. Instead, one has to actually hike around the glacier and the tarn found at the bottom of a hanging gully at 12,400′, and start climbing up Arikaree’s north ridge. For the rest of the route, I wouldn’t be more than a few hundred feet from the center of the ridgeline itself. Even with the above exception, you’re never more than 850′ in distance or elevation from the very apex of the ridge itself.

To my knowledge, no one has completed this trip ever, although there’s been a few who have tried in the last 20 years. There are many variations of the theme of traveling from Milner Pass to Berthoud, as it encompasses much of the Wilderness Land so close to the biggest population center of Colorado and an area that’s extremely popular – there’s a National Park for a third of third of the route obviously, but none of these routes stay even close to the Divide from pass to pass. The L.A. Freeway route goes from Longs Peak, and joins the Divide at Chiefs Head, but exits off South Arapahoe, about 38 miles later, half the actual distance between passes. It’s as close as this challenge is, and I felt like this trip is its spiritual successor. When a Boulder hardperson is looking to prove themselves, this is the route they’ll do it with.

Before Burrell completed the first run of the L.A. Freeway in 2002, Gerry Roach named a still-hypothetical Divide ridge route from the Arapahoes to Longs Peak the Pfiffner Traverse – essentially L.A. Freeway but in the reverse direction, naming after his friend Carl Pfiffner who was a victim of an avalanche accident in 1960. (no one to my knowledge has done this route still, South to North). Still, the name stuck and people seem to call any large trek between these passes a, Pfiffner of one sort of another, leading to much confusion.

But I myself couldn’t imagine why no one had not done the whole thing pass to pass before – the route seems so obvious to anyone living, like me, on the plains to the east of this section of then Divide. There’s an unhealthy amount of extremely competitive hikers, backpackers, runners, and climbers that flock to Boulder to hone in their craft, and these are the local hills. What made it so alluring, but so impossible to yet complete? I also wanted to get away from using the “Pfiffner” appellation, as it’s a cluster of different project that go on vastly different routes – why add to it? My code name for this became Vanishing Point, named after the 1971 B-movie cult classic about getting chased down by the cops while delivering a car in record time from Denver to San Fransisco while drugs and women are somehow shoehorned into the action. I also got re-obsessed with the 1997 song, Kowalski by Primal Scream – named after the, “Challenger” who’s job it is to deliver the car (also a Dodge “Challenger”) to San Fran before said drugs, women, or the cops do him in. The song samples the character Cleavon Little, the blind Nevada Radio DJ of KOW, who can somehow sense Kowalski’s current position and misadventures before even the cops know, and becomes the Homer to the Odysseus of our Kowalski:

And there goes the Challenger, being chased by the blue, blue meanies on wheels. The vicious traffic squad cars are after our lone driver, the last American hero, the electric centaur, the, the demi-god, the super driver of the golden west! Two nasty Nazi cars are close behind the beautiful lone driver. The police numbers are gettin’ closer, closer, closer to our soul hero, in his soul mobile, yeah baby! They about to strike. They gonna get him. Smash him. Rape… the last beautiful free soul on this planet. But. It is written. If the evil spirit arms the tiger with claws… Brahman provided wings for the dove. Thus spake the super guru.

Cleavon Little, Vanishing Point

These lonesome trips in the high country always feel somewhat like a shipwreck bound to happen and it’s easy to find inspiration of being a crew on such a craft.

We arrived at the pass around 7:00pm. I took a nap just beyond the parking lot in a grove of young trees for a few hours, readying my mind for a wake up alarm around 11:30pm. The initial part of the route didn’t have too much technical difficulty, and I felt confident hiking it out in the middle of the night on fresh legs, setting myself up well for when things get a little hairy around Powell Peak, some 20 miles away.

I indulged in my lazy snoozing, knowing that I wouldn’t have much of a chance of any deep sleep while on the route. To make this trip work, I planned to move as fast as I could and have little in the way of extra margins in food or fuel. I brought a minimal sleep system – being alone and with 9+ miles of hiking out to some of the trailheads off route to self-extract if the need presented itself with it’s own problems and I had to know that I wouldn’t freeze if a surprise storm system blew in, or if I injured myself. The sleep system – a cut down pad, a beat-up sleeping bag that used to be rated 35F (pre-abuse), a bivy, a ground cloth/tarp, and because I’m old now: a pillow; clocks in at four pounds. The stove with fuel: one and a half. I also brought a pair of sticky rubber approach shoes. My main trail runners with beefy, but not the best from scrambling. I wasn’t ready to compromise on either, so I brought a selection.

My alarm went off, I gently woke up, and I got my gear sorted out. I walked back to the parking lot to take some touristy photos by the Milner Pass sign, which marked the start of my trip. With little to no fanfare – no one else was there!, I was off up the trail, hiking up above treeline and onto the ridge itself.

The night was warm and calm enough, although the air was heavy with smoke of both nearby and faraway forest fires that dotted all over the west, and I missed out on most of the meteor shower that was happening above in the sky. Coupled with never having walked this terrain before, it made for an eerie atmosphere. Up ahead, a pair of eyes reflected back the light from my headtorch and as I did a sweep around the landscape ahead of me, several dozen pairs joined in. An entire heard of Elk was before me. I had disturbed their own secret midnight escapades. The whole gang moved across my path from east to west, down into the valley below in a hushed rush.

My first named peak came into view: Mt. Ida, five miles into the trip. A new summit for me, although I had tried to summit it last year during a backpacking trip I was helping guide. Threatening weather had instead forced us down into the Julian Lake Drainage to the west. The south ridge from afar looked a little hairy, and some of the crew that day seemed a little tense on trying to get to its summit, then later relieved that they wouldn’t need to. Indeed, I immediately got lost trying to descend that same terrain, finding myself turned around, then cliffed out, then with a feeling of dread: did I actually summit the high point? I seconded guessed myself.

I backtracked back up just to be sure, and finally got cliffed out yet again. So much for feeling confident on the first few miles. I managed to pick my way through the terrain in the inky black night a little west of the ridge itself. The sidehilling back up to the ridge proper felt exhausting and inefficient. What an embarrassing way to start things out.

The next few hours on the Divide fared a little better for me, as I got into a better rhythm. Around the ridge, passing Highest Lake to Cracktop – a little bit of an out-and-back, past some smaller points, and up Sprague Mountain, as the sun came up. With this sun came proximity to the CDT, and knowing I’d pass a few people for the first time in my trip. Flattop was, “summited”. It’s stats are not very impressive: 24′ of rise, and less than a half a mile of isolation. There’s no real mountain, or summit, confusingly and Flattop is best admired from below near Dream Lake, where it’s massive side looks like the hull of a luxury liner. Once up Hallet Peak, I was now on familiar ground from previous trips, and I knew it wasn’t too far to my first water supply and break. Up and down Otis, then a visit to Andrew’s Glacier – or what’s left of it.

I broke out the stove and made some water between Otis and Andrews. It feels somewhat special to take water from a massive permanent snowfield like this in August. The only way this trip works without dropping down into a lake below is to bring a stove and melt the water. It leaves some strategic problems though, as the stove itself is heavy, and the fuel a very precious and exhaustible resource. I felt it worth it – and would do this again the exact same way, as it does save on elevation loss and gain to get down to a damn lake, and keeps the line a little more, “purer”. Being up on that ridge for days on end feels ethereal. The east side generally falls away in dramatic cliffs several hundred to several thousand feet down to the basin below; the west side is usually a more gradual descent into the pine-tree covered valleys below. Staying on this border that’s the delicious tension I was craving.

Cameled up from the snowmelt care of Andrews Glacier, I continued. The goal for the day was to walk out of the Park itself, still 15 hard miles away. The route starts to get interesting just after the summit of Powell Peak. Getting to the summit of McHenrys involves finding a way down into McHenrys Notch, then out of it to the summit itself. The Notch is a few hundred feet hunk off the ridgeline that has long since eroded away, leaving sheer vertical faces on each side, and a 20 foot wide window that makes up the notch itself.

Thankfully, Peter Bakwin and I had done the route the reverse direction on a previous go at the Glacier Gorge Traverse, and I just needed to remember what it was we did! I had watched a chopper rescue take place on McHenrys a few weeks before, so I hope my memory was working well, as I myself didn’t want to be another accident victim waiting to happen. Sadly, as I write this, another accident has already happened in the area, this one taking the life of Steven Grunwald.

My climb into, then out of the McHenrys Notch turned out to be quite enjoyable for me, and I found the right line almost immediately, despite my memory not working all that well. From the summit of McHenrys, it’s an enjoyable traverse across Stoneman Pass to below the third highest peak in the Park: Chiefs Head. Summiting Chiefs Head can feel a bit of a slog, as it’s the opposite direction of where you’re eventually going, and feels a bit like an out-and-back, but the Continental Divide indeed follows up the broad ridgeline up to its summit, both on the northwest and southeast side.

Chiefs Head also marks a milestone in the route, where one finally leaves the shadow of the extended Glacier Gore drainage which I’d been traveling all night and day and you enter into the Wild Basin drainage, where I’ll be traversing above for the rest of my time in the Park. Wild Basin, in contrast to Glacier Gorge is relatively quiet and unpopular – the access is just that much longer to get to the Divide. Good for someone like me that revels in solitude. With the quickly approaching evening, solitude would be a given.

The march towards the next major milestone, Isolation Peak, takes a curious path. The romp up Mt. Alice is Class 3 at most, then drops down to diminutive Tamina Peak, before challenging you with The Cleaver’s route finding puzzles. I managed to pick up some honest to goodness water I didn’t have to make right before The Cleaver. A melting snowfield was shielded from the sun to the east by a large tombstone of rock, leaving a small puddle of water that elk in the area had been taking advantage of, evident by their hoof prints and droppings. I thought it wise to take advantage of it, too.

There’s a more or less direct way up Isolation Ridge right after The Cleaver, but I hadn’t been able to figure it out on my recon trip a few weeks before and wasn’t about to try it now that I was on the actual trip. All I can say is: either I’m a worse climber than I think I am, or there’s no direct, 5.2 route as the RMNP climbing guidebook would suggest. Both are debatable. I took a Class 3 sneak on the west side that I’d thoroughly sussed out. As I made my way up to the summit of Isolation Peak, the sun set over my right shoulder and I was left in the dark with my wandering thoughts.

Isolation Peak is the farthest and most remote peak from a paved road in the Front Range, which is notable, but the mileage is less than seven, which is bittersweet. The only other peak that’s farther from a paved road than Isolation in Colorado is Rincon la Osa in the Weminuche far out in the San Juans. We have as a civilization have encroached so close to what we have deemed, “Wilderness” with our modern conveniences such as roads, and that’s particularly easy to see on the Front Range, as with the night come the lights of the towns and cities flickering in the distance.

With Isolation behind me, my mental acuity went downhill, fast. Alone, as far I could possibly be from really anyone, I started to have a hard enough time just understanding where the ridge I was following even was and separating it from ridgelines that simply decended into the basins below. The darkness and smokiness of the air not being my best allies. My high-powered head torch had difficulty cutting through the haze and nothing looked familiar to me, even though it wasn’t that long ago that I had been on this part of the ridgeline during a recontour. For the next few miles, as I labored towards Ogallala with heavy eyelids and steps, I caught myself walking in circles. Stubborn on keeping my goal, I wouldn’t stop until I had reached beyond the Park borders. I liked the concept and looked forward to saying that I had, “Walked out of the Park” in a day.

Finally Ogallala came and went, and I stumbled down the ridgeline a click or two to find shelter from the wind behind a low, flat boulder; almost 24 hours from when I started. I set up my tarp on the tundra, and bivy/pad/sleeping bag on top of it, and passed out for a few hours, to awaken before sunlight hit my face.

At 6:35 am I was up and moving and the second day would start out much like the first: the hiking wasn’t too difficult, but I was now desperately out of water. I left with only two 24 ounce bottles, had a refill at Andrews Glacier, and some water at the melting snowfield, but that was all my water intake for over 30 hours.

Thankfully, the glacial wall of the St. Vrain Glaciers reached almost all the way to the ridgeline at 12,500′ up and I was able to scramble down just a few feet to reach the top, shovel the frozen snow into a stuff sack with the stove pot and bring it back up to the ridge to make water. The air felt crisp and cool, although the smoke settling into the valleys to the west was heart sinking. To keep as light as possible, I didn’t make much – just enough to fill up my two water bottles again.

The route to Algonquin is mostly tundra walking, with a few interesting points where the ridge narrows and gets a bit scrambly, but generally, it’s a cruise. The tundra is rocky, so attention has to be kept on the way ahead. Once on Algonquin, things change rapidly, and the route won’t feel so simple for many miles onward. Only a mile away, Pauite Peak dominates the view. That entire mile of ridgeline is one huge scramble up, over, and around spires, towers, and gendarmes. The rock quality is not always great.

I wasted no time in getting to it. In generally, one stays to the west side of the ridgeline, where grassy ledges can be linked up to get around the hardest of terrain. The last tower is the largest, most difficult, with the worst rock, and the most devious of route finding. Generally, I switched up and stayed on the east side of the last tower – there’s no way to go up and over it without a rappel on the south side – I’ve tried before.

The terrain around this tower is gravely and sloping, and the last bit to safety is a squeeze around a corner into a chimney. At one point, the rock my left foot was resting upon gave way, and rocketed towards Coney Lake Creek, leaving behind it the heart sinking echo of rocks crashing into themselves, and a smell akin to gunpowder. The majority of my weight wasn’t resting on that rock – I must of been toeing off to take a step, so I didn’t stumble or fall, but listening, watching, feeling a rock that large take a tumble at terminal velocity always makes me a little uneasy.

I scrambled down the chimney, and looked up at the final route up Pauite Peak proper. The rock quality gets much, much better and the view of Pauite from this vantage point really is an awesome sight. Snow sneaks up the steep, narrow gully below me, and the ridge shoots up with considerable steepness. A few hundred feet above me, a great secretive north face flirts within view. A stout scramble up a series of ledges begins the ascent, then up a steep open book that skirts the main face just the east. Hiking territory on loose gravel will take you up and around a fortuitous sneak up another open book with delightful movement.

The last bit is the loosest and weirdest, as you need to climb up yet another small chimney pitch. This chimney is right below the summit, and I’ve practiced completing it both up and down on two separate trips at least a dozen times, so important I thought it was to get this part done solid. But I guess I forgot to practice it with such a large pack, as my beta wasn’t working out – usually stemming up a chimney isn’t easy with such a pack. This pitch isn’t hard, but exposure off to the north is fierce, and a tumble isn’t on the agenda for today. I revise my beta, sticking to the outside of the chimney on some slabs, and continue on my way to the summit of Pauite.

From Pauite, one gets a grand look at the rest of the day, with peaks littering the view. Things don’t let up for a summit of Toll, a bop over to Pawnee (and bonus peak, “Pawshoni”), then Shoshoni. Afterwards it’s a match on the Kasparov Traverse to Apache, then finally: Navajo. There may not be too many places in Colorado’s alpine that have this much scrambling packed together. I’m pretty excited, looking from Pauite out over all the terrain in front of me. This is really what I’m here for.

Mt. Toll is a grand tower – very unique to the local terrain, and its North ridgeline provides excellent scrambling on good, gray rock. I chose my own adventure up, having lost how to do the coveted chimney pitch, but it’s workable way to get to the summit.

The Kasparov Traverse is a point of nervousness, as its easy to get lost in the sea of rock you need to wade through. I mostly stick to the east side, traversing grassy ledges and avoiding “The Chessmen”, a series of towers of varying difficulty, which aren’t apart of this project. I had the hardest time figuring out the very first moves to start the traverse in earnest, but after that, things were mostly smooth and my rehearsed route worked out for me wonderfully for the most part. I did traversed below the King’s Pawn a little lower than I had sussed just a week ago, but it worked well enough, and I was on my way to Apache, as the sun was seriously starting to dim.

Dim, as in: the sun was up in the sky – it was only around 7pm, but the light coming from it was diminuative – the smoke being so bad. This complicated my day, as I needed to see my way through Navajo’s technical north face route, and its finger crack summit pitch. If I couldn’t see my way through, there was an alternate, easier route that wraps around from the west, but I hadn’t done it in five years and I wasn’t looking forward to relearning it on the fly. I made my way down Apache’s summit with tempered haste.

At the base of Navajo, I made the call to do the north face, even with the failing light. If I climbed quickly, I’d just beat out the proper sunset. The climbing here is just so much fun, even if my mind was getting fatigued, aided by the smoke in the air. At the very crux of the route, I completely blanked on how to pull it off, and hemmed and hawed for what seemed like an hour, but most likely was just a few minutes. I found the key hand and footholds and was on my way. The summit pitch is more technical, but sometimes that just makes things easier to remember – and it feels more like a boulder problem than a long pitch of climbing. The latter of which seems to work better with how I process terrain.

On the summit, the sun now was seriously down and I was facing a bit problem. I was out of my mind tired from the effort of the day, and I was facing a long stretch of terrain I knew nothing about and wasn’t particularly stoked to bivy in. Faced with these issues, I decided to call it for the day. I descended a bit down towards the airplane gully – a descent route off of Navajo (a terrible one), found a rock wall and somewhat flat, somewhat coffin-shaped pit of gravel to lay on, right next to a diminutive snowfield I could make just a little water from with my stove.

At over 13,000′, this would be my highest bivy of my trip, and one of the highest I’ve done in Colorado. Thankfully, it was protected enough from the wind, but not from the smoke. Tomorrow was another huge day, but I was happy, even though my estimated timeline was slipping – it wasn’t even 9:00pm – a relatively short day!

I was under the impression I would already be on South Arapaho before the end of day #2, hoping to have been bivvying behind the wind screen on that very summit, but that was miles further away – all of the terrain to be done in the future being difficult scrambling. This was no real problem – my goal was to finish, and since no one had finished before, I was setting a baseline time. Maybe if I had done the terrain before I’d have the confidence to do it in the dark, but I hadn’t. For a future bid. But this also posed a problem: the amount of food and fuel I had was finite, and an extra day out meant 4000+ extra calories I couldn’t just magically find in my pack. I’d have to start rationing.

Another before-sunrise start at around 4:10am, began with a decent into chunky moraine to the glacial tarn of the Arikaree Glacier. I could have sworn I saw the headtorch far off near the edge of the hanging valley – it was so precise and bright. Haunted by it, I turned my light off, in hopes to deter anyone trying to track me. It took me a few takes, but it was no headlamp – the sky had cleared up and what I was looking at was the reflection of a star or planet in a mirrored pond! Pre-coffee Justin is a fantastically dumb beast.

I took some major gulps of the water at the glacial tarn, taking in the atmosphere of the entire glacier surrounding me. I first had to crack the thin surface ice covered. It’s no stretch to say that this water was some of the best water I’ve ever tasted in my life. I almost didn’t want to leave. But there was more – much more route to do.

I made my way to the north ridge of Arikaree not know exactly what to expect, and soon found myself in trouble. The terrain here is steep, and seemed too loose to be a route of any utility. The sun wasn’t yet up, and I felt ridiculous trying to feel my way through the rocky ledges. The main ridge seemed implausible, as it seemed to keep towering out above me, but everything else around was just as easy to dismiss as a good route. At one point I found myself in near vertical terrain holding onto jigsaw puzzle-like hand and foot holds that reminded me of the last part of the first pitch of the First Flatiron, except grubbier and miles from nowhere. I slowly retreated from a stuck point and reevaluated.

I finally woke up a little more, and decided to stick to the main ridge. After a few committing moves in the early light, it turned out to be a most excellent way to go. I’m sure the next time around (if there’s a next time), this session of faffing about will all seem cruiser.

Soon the summit of Arikaree was topped; the other side of the peak being a very simple and straightforward talus hop down. The disparity between the two routes of opposite sides of the mountain left me speechless. There’s a few minor ridges to wander over, until a larger peak with plane wreckage is found at the base.

After the long debacle of getting lost summiting this small peak above and back to safety, it was a nice hike onto Deshawa. Around here I bumped into Ryan and Nick, who may have been just as surprised to see me as I them – who would be out here? I knew before we even started talking that they were out doing their own recon of The Line. I told them what I was up to, and they first didn’t believe me! But the reality soon set in, and they wished me luck, albeit a little bitter-sweetly as they’d hopped to nab the first thru-hike tour on the Divide between passes in the coming weeks and here I was stealing that thundering at a limping pace. Little did either of us know that someone else had already started on the route way back at Milner, and they would finish their own trip five days later! Left alone until this year, and now all this attention given to it. Something in the air, I guess. As a small token of goodwill I helped Ryan and Nick on a little of my own routefinding beta for their own go at the line.

The views down this immense valley are some of the most outrageous I’ve seen in Colorado, and certainly some of the most unique of all the Front Range. It’s a pity that this area isn’t so welcoming to visitors. The route up Deshawa is just a delight, and it leads to the north ridge of North Arapaho, another unknown treasure of the Front Range. The traverse from both peaks rivals the traverse from North to South Arapaho by a country mile, which is also about how long this traverse really is. Just great terrain to move on.

Once on North Arapahoe, I could breath a little easier – or try to breath a little easier – smoke was thick in the air. But the difficulties of the route were almost over. I had a small trip to South Arapaho, then an unpleasant descent down towards Quarter to Five Peak, and a perfect scramble up to Neva.

As before, I’ve had already sussed out the route off of South Arapaho, following the Divide closely. It’s terrible, but it’s far more direct than taking the trail down South Arapaho’s east ridge, then circuitously going down below Quarter to Five Peak, so the main line it was. And of course, I flubbed it up . An easy thing to do, as the gullies leading down South Arapaho have a tendency to fork off from one another, and taking the wrong fork down means finding oneself in the wrong drainage. There’s rarely a way to go from one gully fork to another – the cliffs and towers block the way, so it’s a backtrack back up the slope, with tail between legs.

Quarter to Five Peak is a point far below the two mountains it sit between, and I’m not sure which one of three of the high points is the actual peak. I was greatly looking forward to visiting Lake Dorothy, a high lake located at over 12,000′ in altitude, right on the divide and just a few trail’d steps further. Fed by a permanent snowfield, the historical retreating glacier dammed this lake behind a terminal moraine and it has stood the test of time.

I took a big break here and sunned myself on a flat rock that jutted out into the lake, and cameled up with water that would hopefully last me for the rest of the 30+ miles to the finish. Most likely, the second-best water I’ve ever drank, but that’s certainly circumstantial. My delight in this oasis was somewhat dampened by what looked like a huge storm developing off of Longs Peak, and coming towards me fast. But it wasn’t a storm per-say, but another forest fire, this one near Cameron Pass. So large, it created it’s own weather system around it, and this is what I was witnessing. The clouds though, weren’t going directly my way, and I would stay dry, yet smoke was all around me – not just from this fire. I’ve never experienced anything like this, so I have little to compare these conditions to.

Mt Neva was next, and the scrambling here is delightful. For all the popularity of the traverse between the Arapahos, it’s a mystery why Neva doesn’t get its due. The route is far more interesting, engaging, and beautiful. The hidden, red marble and white quartz north face is jaw dropping. The route goes just to the edge of this face and the scrambling is primo.

With Neva summited, it really is just a long, off-trail hike to Berthoud Pass. All the technical difficulties are over. Can I just keep moving forward? The day was already slipping by, but I made a goal to get to Rollins Pass – a lowpoint in the route at 11,676′ and a fine enough place to bivy, even though anywhere else on the route would literally work just as fine – the line was now a gentle giant.

There are only a few points to be summited in this stretch and one of the largest, Skyscraper, is really a bonus peak. As I hiked, I watched airtankers take off from the Denver region, fly above me, and bring their payload to a nearby fire to the west. They made their rounds around every 20 minutes or so. Seemed like every turn on the route, another fire sprouted up. I wanted to finish up this trip, as I knew this smoke was not a great thing for my lungs. The thought of having to finish this trip in a full asthmatic attack wasn’t very attractive.

The sun soon slipped behind the fire blazing to the east – is the day over already? And I dragged my tired feet towards Rollins Pass. I picked up the CDT, but the tundra I left behind was easier to walk on, so this wasn’t met with much excitement from me. I stumbled on the loose rocks found on the trail and looked around for the trailhead info sign to call it a night.

I bivyed near the foundation of an old building at around 10:00pm. A cold night for a change, and almost at the limit of my gear. It felt peculiar to have gotten to Rollins Pass traveling from the north, as I’ve only traversed across Rollins Pass by bike from the east to the west. It felt familiar, but my bearings were off on where exactly I was. But I had finally hiked through the Indian Peaks Wilderness – it was a wild ride – it took a full two days!

I got up again at 4:30am for hopefully my last half day on the ridge, and marched towards, “Hell Hill” – the highpoint of the ridgeline that Rollins Pass sits upon, and a colloquial name the railroad workers gave the pass itself. Trying to maintain a railroad up this high on the Continental Divide seemed to have proven troublesome.

As I entered the James Peak Wilderness, the sun lazily began to rise, and I enjoyed the simple act of walking high on the Divide, overlooking the sheer cliffs to the east of drainages that I knew nothing about. Some of the faces looked steep enough and high enough to base jump off of. The smoke was thick in the air, and it seemed as the sun rose, the smoke just gained in viscosity.

James Peak is the high point in the area I was now in, and proved to be the only formidable challenge. I was simple tired, and the walk up to the summit was a slog. From the summit, I should have been able to see the end of my route, but it was so smokey that this seemed to not be possible – it’s as if I was looking at a living drawing, and the artist just hadn’t gotten to the background yet – everything just faded away, barely sketched out. Not really knowing where I needed to finish up, I had to imagine that it was really out there, somewhere south of me, and to trust that if I kept going, it would be waiting for me. But the line between imagination and reality was very blurry.

The Class 3 ridgeline from James Peak to Mt. Bancroft provided the last opportunity for excitement, but pales in comparison to the difficulties left far behind. I was joined by a CDT hiker for the rest of the hill bopping, all the high points somewhat blurring together, as things turn into gentle rolling hills. Somewhere in the distance, I could finally make out the communication towers on Colorado Mines Peak – the last highpoint of the ridge before Berthoud Pass, leaving me to feel extremely elated.

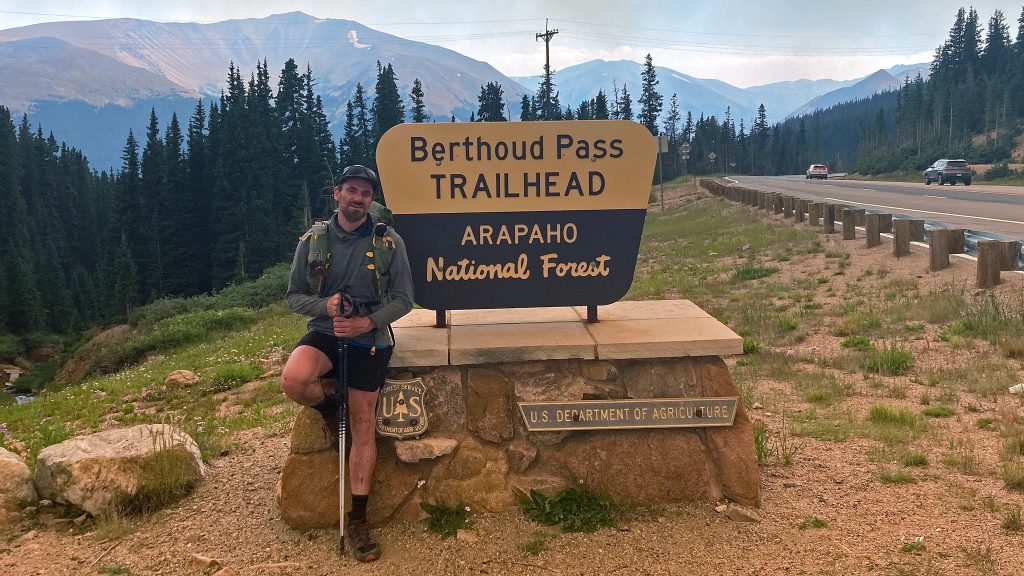

The now-gentle terrain gave my head a little space to meditate on the entire trip I had just taken. I took the small hike up Colorado Mines Peak from the access road, summited, then dropped down to the parking lot, feeling again pavement under my feet, and visiting the wooden Continental Divide sign for yet another photo next to it.

And really, that was it. The line had been completed. Fourtuitously, friends where on the summit of Parry Peak, right after Mt. Bancroft, and once they were done with their own trip for the day, we all drove back to Boulder – even my new CDT hiker friend decided to take a break from the smoke and hang out for the weekend in Boulder. Back at home, I orded an enormous pizza and we all relaxed back in the safety and security of this old farm house I call home.

[…] Vanishing Point […]

This is so good. I’ve done most of the non-technical parts of this traverse in bits and pieces over the years (though I’m still 0/2 on Isolation). The idea of going to doing it all in a one pure push without dropping down for easier water just blows my mind. Thanks for the vivid descriptions.

Brilliant write up to an even more spectacular feat! I’m stoke you were able to be the first on this geometrically pleasing feat Thanks for adding in the historical notes and your own guideline on what you deemed was successful.

I liked the way you phrased Colorado this summer “it’s as if I was looking at a living drawing, and the artist just hadn’t gotten to the background yet”. So I’ll bite, what’s the best water you ever drank?