2:00 am is a hell of a time to wake up, especially when you finally went to sleep at a little before midnight. Probably. I now wake up and think about my immediate surroundings. They seem almost Thoreau-ian – if the surroundings weren’t in their own immediate surroundings. I’m wrapped up in a sleeping bag, on top of a beat up sleeping pad that has slightly less patches holding it air tight, then countries it’s been placed on the ground of, all in a room just wide enough to outstretch my hands and not touch the opposite walls.

Around me are a few books and grey containers of mostly clothes, with a few pieces of choice gear. Not much else. I don’t really have much else. Although when I close my eyes, I like to fantasize I’m in a much more ethereal setting, I’m really not. I’m not in a small cabin in the woods, I’m in a very cramped, converted, “room” in a house – just big enough for me to sleep in – and afford, located in the outskirts of Boulder, CO. I’m living in the proverbial “closet”, that so many others before me have taken residence. I’ve moved here recently because I love the mountains and being 10 minutes away by bike sure sounds a lot better than an hour away by bus.

I get up and start dressing. It’s cold outside. Well below freezing as it usually is during Winter. I put on a my bike bibs, two base layers, and running tights. My legs look like deliciously swelled sausages. The type I’d love to eat right that very second with some eggs, maybe even some toast. I’m skipping breakfast – a horrible mistake, and continue dressing for the bike ride. I dress my upper body, and put the rest of the clothes I picked out in a small backpack. I Double check I’ve got my hiking crampons and an ice axe. I slam down some reheated coffee, throw a few handfuls of almonds in my mouth, and we’re out the door.

From Boulder, the bicycle ride up to the Longs Peak Trailhead can be divided into two sections. The route to Lyons is undulating, but mostly flat. It follows the dividing line between the prairies and the mountains, running South to North.

Once in Lyons and in St. Vrain Canyon, it’s a stiff climb up 9,500 feet to where the turnoff to the trailhead is found: right on mile marker #9 of State Highway #7. The mile markers count backwards from Lyons, which adds to the psychological toil of gaining more than 6,000 feet total that you will have to complete by slowly turning the cranks of your bike at maybe 10 miles an hour, if you’re really jamming it. A long way to go in the middle of the night, but quiet. There’s hardly any traffic on this mountain road, and much of it is going the same place you’re going. There’s not too many other places to go.

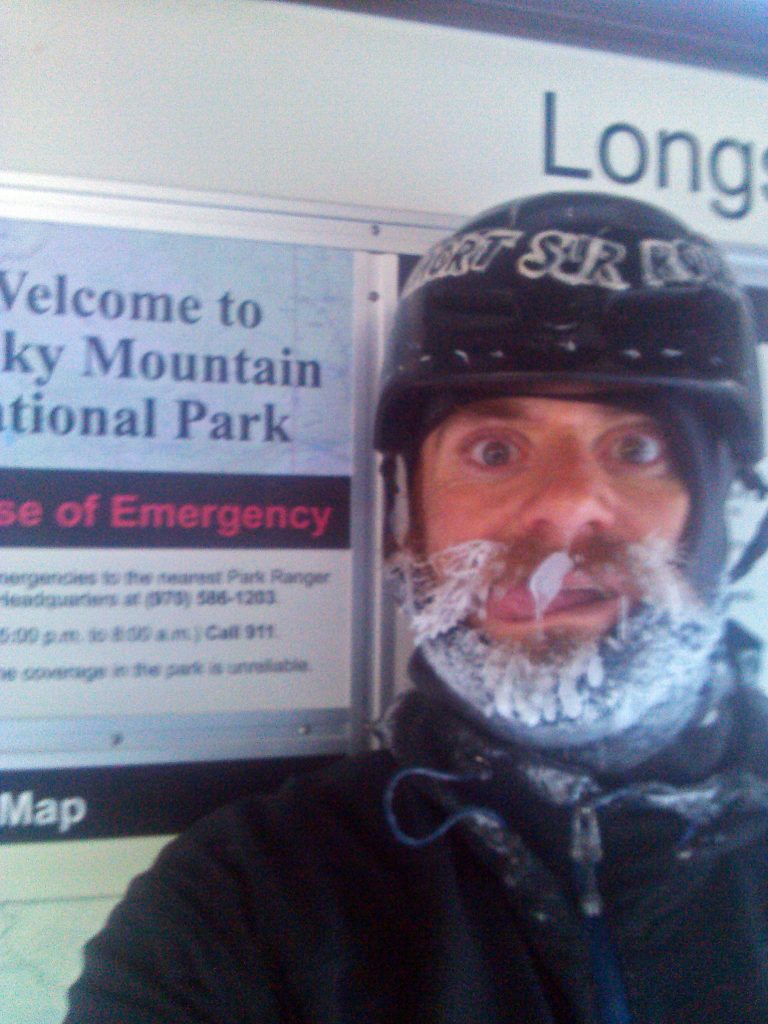

With relief, I make it to the trailhead a little past 7:00am. I am astounded. Not only because that’s a really good time, considering my sleepy head, my heavy bike, and a load of gear, but also because my face is frozen – completely covered in ice, from huffing and puffing in then cold, and what seems like humid air. I’m picking icicles from my face, as I reorganize everything for the next part of this trip up the mountain.

A few people are milling about – they saw me coming up as they passed in vehicles, and everyone’s friendly in the entrance way of this overgrown outdoor playground. Two people are set to climb The Diamond (D7), a tough goal for winter.

“That’s pretty crazy”, I respond.

“Yeah”, one mocks back at me, “Wanna look at what you’re doing?”

They have a point, and I can appreciate their gentle ribbing, as it creates camaraderie out of our fairly different goals on the same mountain. I realize that in time, I could attempt what they’re doing if I wanted to, but for now, I’ve got my own ideas to work on.

I’ve yet to be successful at all this, although it’s been a goal of mine this winter: summit Longs, by riding there by bike (and back) in Winter. One big push. Today will be my third try this winter. The weather has been the deciding factor. During winter, it’s default is to be horrible on Longs Peak: cold, most always windy, sometimes snowing.

Dangerous.

On my second try, I was beaten back by winds so harsh, they stopped me from even walking forward. I was in total disbelief that wind could be that strong. Sure: maybe in a Charlie Chapman silent picture, you’ll see the Little Tramp beaten down by wind, but certainly that can’t be in real life, outside of a hurricane or Antarctica. I was mistaken. Winter is drawing to a close and I’m running out of time. This could be my last shot, the weather could turn ugly once again.

I start up, and immediately regret not eating a proper breakfast. I’ve had almost nothing to eat today, and my energy level is already really low. I imagined the night before of making a huge feast of half a dozen eggs, strips upon strips of bacon, and corn tortillas to wrap it all in covering my plate before taking off, but the kitchen at the house was in a state of duress from my room mates, so I sort of: gave up and ate something more modest, before hitting the hay. That quick bike ride up may have also been a little too quick – I may have burned all my matches, already. A rookie mistake to do, already to find myself in a state of trying to maintain my condition, rather than excelling after all the work I’ve put into becoming stronger since the beginning of the year.

I trudge up through the Enchanted Forest. My boots don’t feel right. I quickly take them off to inspect, but find nothing.The boots are fine. My feet are what’s the problem. They’re numb from the cold bike ride in certain places, but not all over, causing the strangest of sensations. I choose to ignore it. It’ll either fix itself, or it won’t. If it won’t, I can always go down.

Well, hopefully go down.

The day starts turning out to be actually really nice. Sun’s out, the wind is low. The East Face is basked in the alpine glow reserved for such rare days, and to those who are up early enough to catch it. I realize I may do the almost impossible: I have threaded the weather window needle between storms, navigating it with my own busy work schedule and all the other crap that gets in the way of such fragile little dreams.

I feel less than ideal, and everything feels too heavy – and my objective too far away. But, I continue on, making it to the trail junction, and find the trail to Granite Pass filled with snow. Makes travel slow. Being impatient, I leave the trail and boulder-hop up the side of Mount Lady Washington, to take a shortcut, passing over Lady Washington’s shoulder and into the Boulder Field (everything here has a name). The trails here are on the questionable side of meandering, and aren’t specifically made to make my objective easier. The signs are well-known to also post the wrong mileages to their destination, further confusing matters. In wintertime, when the tundra is protected by snow, it’s sometimes better to just forgo them completely.

My shortcut is shorter in distance, but eats up time, as my line is far from straight. I turn the corner of the saddle – finally, and get my first look at the Keyhole, my next objective. Between myself and the Keyhole is the Boulderfield, which sounds benign enough, but it certainly seems to be the crux of this whole jam.

The Boulderfield lives up to its name (A field! Covered in boulders!), and is further augmented with a thin blanket of wind swept snow, making most of the boulders invisible. You walk a bit, hoping to you can hop from boulder to boulder, and then, whoomp! you find yourself plunging knee deep in snow, missing the mark, falling over. It’s an energy draining ordeal and there’s nothing much to do, but endure. The North Face is just south of the Boulderfield, and allows a quicker and more direct way up to the summit, than the Keyhole route, which spirals three quarters around the mountain, following the weakness of the ledge systems of the Western facing side of Longs.

“If only I had a rope”, I think to myself, “get right up this Mother”. Then I realize my place: I have no rope, no experience using the rope: I don’t even know where the pitch that makes, “The North Face Route” is. I continue my trudge. I’m happy to make it this far. The headache starts.

I pause at the Keyhole – it’s a very dramatic spot, as the entire mountain changes characteristics at this very point. I grab my camera, to turn it on but, it’s dead. Looks like I forgot, “put battery back in camera” on my preflight checklist. You always forget something.

The ledges of the western side are dolloped with snow, and look exceptionally foreboding and untrustworthy, with no obvious way through. I check the time (later than I’d like), and how I’m feeling (headache, weak, tired, sleeping, hungry, but otherwise: OK) and decide to play a dangerous game of, “What can I go without”, with my backpack full of gear. I decide, somewhat inexplicably, that my actual waterproof, warm winter pants can be optional at this point and that I’ll just stick to long underwear and running tights. My hooded, warm, puffy winter coat also doesn’t make the cut. They’re some of heavier items, and if this beast is going to be finished, I’ve gotta get faster somehow.

My boots, I now realize, are soaked. The gaitors I’m wearing are useless, allowing only for snow to come in from the top, then working hard to keep the snow close to my feet, allowing it to slowly melt, trickling into my boots, soaking my socks. Each step is making slightly perverted squishy noises.

It’s a bad situation. I have an extra pair of socks I’ve brought, but decide not to change into them, I’ll just soak those right through and have two pairs of wet socks to work with – I mean I still have to get back down. Back down to Boulder: I can’t ride a bike in winter, from 9,500 feet, at night, with frigid feet. It’s one of those, “Nothing makes sense” scenarios. The extra socks stay, too. And oh – that useless camera.

Beyond the Keyhole, the route follows a whimsical path of the various weaknesses in the otherwise foreboding landscape: The Ledges wind you around the mountain, without any gain in elevation to The Trough; a wide, rocky couloir that brings exits you to the Narrows; a well – narrow set of ledges, which takes you to the beginning of the end; Homestretch, a slabby bit of rock to scramble to the actual summit, the only real weakness to reach the summit – everything else is a true alpine pitch.

To help matters, the route is littered with bullseyes spray painted on the very rock, so that you know when you’re on route. If you see a bullseye, you’re golden. If you don’t, you could possibly become cliffed out. What complicates matters in the winter is that if you don’t see a bullseye, you could be either off route, or the bullseye is close, but just covered by snow. It’s a head game, for sure.

I have to remind myself that I’ve actually never done this route before. It’d be easy to know the general feel of the route, but I’m just as lost as someone who’s just beginning.

It keeps thing spicy, and at this point, just another detail to work out.

And sure enough, it only takes a few hundred meters, until I’m most certainly off-route, in a way where I don’t know where, “on-route” is, except it’s not where I’m at. I think. The landscape around me is surreal: there’s giant pinnacles of rock that I could need to go through or around – and almost want to just for the hell of it. I look towards the summit, and there’s a couloir, but not the one I want. On top is a rocky spire, that looks like a chess piece. No one is around me, but the entire place feels very much alive, basking in this cloudless afternoon. This is what keeps me coming back to this place – it’s one of the most beautiful mountains I’ve ever seen. The sun though, is terribly strong today, reflecting off all the snow. My headache is getting worse, and I feel my fare skin start burning.

Besides being off route, my biggest worry is the short stretches of snow slopes I need to traverse. There’s no telling if they’re stable, but I err on the side that they’re most definitely not, and keep my time on them short and my footing nimble.Avalanches are nothing to joke about in Colorado, and winter is not a very stable time for the snowpack. There’s been about eight deaths by avalanche in Colorado alone this year.

Big problems happen when snow is blown into gullies and couloirs. They become a wind loaded pile of snow, on top of another, unstable layer of snow. On the west side of Longs, everything is wind-loaded, if it wasn’t it would have been blown away by now. I keep that in mind. I tell myself that the snow wouldn’t be there, if the terrain underneath it hadn’t some sort of characteristic to trap it there – ie: there’s a ledge underneath, or rocks or something. The parts of the face that are smooth and totally featureless, I notice, are without snow.

I get to a point in my route finding, that I’d definitely would need to pull some technical moves to surmount the obstacles in front of me. Getting to even this part required some, shall we say: creativity. My dull mind is slow to realize that this means that I’m very much off route, and about to get myself into a jam, as some of these moves are too delicate to reverse in my conditions and I look for a sneak of an exit, so I don’t need to backtrack so far. I take it in stride, as I’m much more reticent to the idea that I’ve put myself in this position to start with, and anyways: all that rock climbing I’ve done this winter has given me confidence that I didn’t have before.

I find one way down that leads to the Trough, but it requires nimble footwork in a no-fall area. To pull it off, I need to reach with my right arm, while stepping with my right leg, pull my left leg in, bend that knee and push off with my left heel, while reaching for another hold with my left hand, pivoting on my right foot. Like a ballet dancer, I guess.

From there, I’m facing the rock I’m holding onto, and I’ll have to drop down and hold onto the ledge with my hands I was just standing on. I go for it, since, what the hell, but my pack is too bulky and gets in the way, as it scrapes the cliff face. My balance is off and I can’t swing my left hand over.

Now the problem is, I can’t get my weight back to the starting point, as my left foot has fully committed to going forward with the plan, and my crampon’d boot is not agreeing with finding a better purchase on the small foothold. It’s of no use to make a contingency plan at this point: if I fall, I want a clear mind, so I instead just finesse my way back to the ledge. There have been times when I would have escape this sort of brush with danger, and then quickly hyperventilated until I was at the point of sobbing, unable to move from my prostrated position, but I’m well aware of what I’m doing and accept it as part of it all. I’m at a temporary safe space, anyways.

I make a mental note: “Not the way to go”. I look over about 10 feet away, and there’s an easy way to overcome the obstacle I had missed, and I take it without much fanfare, reaching The Trough, which is a straight forward climb up, and feels very safe in comparison to the snowy Ledges. I imagine throngs of people on this part of the route in the summertime heat, but on this day, it’s only me – I literally cannot see anything man-made on the horizon. It’s a wild feeling.

The Narrows also come easy, as they’re not as narrow as you may imagine, and are bare of snow most of the way. Homestretch looms, and I’m happy to almost be done with this. The snow on it has been sunbaked for hours, and slipping here affords no break for hundreds – thousands of feet down Keplinger’s Couloir, but I plunge my axe down, take two steps, breath three, four, or five breaths, and repeat until I get to the summit. At last.

The very top is something it hasn’t been all day for me: windy, and I get cold almost immediately. As much as I want to linger and take silly photos, time is getting tight, and I’m now faced with dealing with my rash decision of going for the summit so late in the day: I may get stuck on the technical part of all this, after the sun goes down. I can’t even sign the summit register, the canister the register should be in is cracked and broken.

I change into some warmer clothes: basically, the ultralight puffy jacket I did decide to bring. I take a look at my gaitors yelling some quiet obscenities, making due to try to get them in better shape. My boots are now completely soaked, so it doesn’t matter anymore if the boots get any more moisture in them. Snap a few photos with my phone to say, “yup I was here” somewhat unceremoniously.

And then I’m gone.

Now that I know the general lay of the route, the landmarks all come and go relatively quickly, and it warms up considerably with the lack of wind. I make it to Keyhole and retrieve my cache of gear. I sigh, as I look at the Boulderfield. The shadow of the mountain casts itself almost all the way to Mt. Lady Washington’s west face, and it’s going to be race to see if I ever feel the warmth of the sun before dropping over to the other side.

It’s close, but I make it with a few minutes to spare. From then on, I’m in shadow and it become cold, the wind picks up, and I descend the east side of Mt Lady Washington, stopping as spindrifts engulf me. The wind is again picking up steam.

It seems to take forever to make progress, as I’m tired, and my steps are awkward. I slip a lot and fall. There’s no real danger, but it slows me down, and is frustrating. I’m starting to lose my sense of time, and distance – I’ve escaped falling off any literal cliffs, but I’ve plunged down deep mentally. Everything looks enormous around me – I always forgot how large Lady Washington really is. I imagine myself farther down the route than I am, and am let down when I find hard evidence that I’m not. My lack of sleep is starting to catch up on me, and my brain is bartering for a nap:

“Twenty minutes”, it asks, “Just give me twenty minutes to lie down, somewhere. Over there is fine.”

But I deny myself any sort of rest, knowing that the winds are picking up, the temperature is dropping precipitously, and I’ve got much more than the hike 5 miles out to the trailhead, before I can call it a job well done.

The hike through the forest is unending, and I’m now using my head torch to light the way. I’m starting to hallucinate, as anything that isn’t snow could very possibly be well: anything. I miss some of the shortcuts and yell at myself for doing so, but I’m too tired to backtrack, and too confused to even know if I’m on the right trail at all. I find myself most definitely not, but I just give in that down is a good direction to go towards. I have nothing to look forward to, but a 45 mile ride back to the house. My feet are still swamped with water. As I hike down, I’m executing in my head exactly what the steps I need to do when I get back to the bike, to keep warm, and better my situation. It’s not life-threatening, but I can make the ride down either miserable, or just something I have to deal with in my fatigued state.

I reach the trailhead and begin my plan. Gaitors come off. The moisture on them instantly freezes, so I beat them across the picnic bench to break off as much ice as possible and set them aside. I take off my boots and quickly take off my socks and put the fresh, thick, dry pair I’ve been frugally saving finally on,and put my bike shoes on right afterwards. I then put on the booty covers on the shoes, and then put on my snow pants, then the gaitors. My bottom half is relatively warm, but I need all the help I can get, as I’ll reach 40 miles per hour, simply coasting down St Vrain Canyon. I layer up my top in a similar way: wool base layer, wool mid layer, puffy ultralight and my winter coat.

My gloves are my only other worry: like my socks, they’ve been soaked for most of the day. I’ve relented in taking them off at all – there’s nothing to replace them with – no drier pair, so my only hope has been to simply will them dry enough, so the wind chill factor won’t freeze my hands. Frozen hands equals uncontrollable bike equals no brakes and no steering. Somehow thos plan works well enough, and I thank myself for not going exceptionally ultralight with my gear choices today. It could have been bad.

I don my baklava, helmet and I’m out of there, again unceremoniously. What was once so inviting with a rising sun and warmer temps is plunged back into a harsh winter scene, ready to deny anything close to charity. My hope is to make it to Lyons before the town shuts down to just get something to drink, water – a Red Bull: whatever. I’m out of water. There was a creek near treeline that I had a few gulps out of, but in my altered state, I thought it unwise to bring any down with me – coulda slowed my already snail pace down. Now, it’s going to be hours until I can have a drink again.

The highway through St. Vrain canyon is mostly desolate of cars, but it’s dark, and my batteries are failing on my lights. I decided not to pedal too much – and just coast, see how fast I can go down, brake as little as possible, and surf that edge of being in control. My whole mind is dim and my eyesight is failing. Contacts are dirty, having not been properly cleaned for who knows how long. The entire day of being exposed has done its number on them, and they’re checking out. I let out one of those laughs you give, when you find yourself in these sorts of positions. Truly uncomfortable, but honest with yourself that it was your idea to do all of this. It puts a smile on my face, and I get a song stuck in my head, trying to sing along.

I miss the entire town of Lyons being open by five minutes, and take it that it’s going to be another 15 miles till I get a break, and can drink something potable. The road is now fairly flat, with small climbs that all seem like their own mountains to my tired body. So very few lights, and no turns in the road, I lose all sense of where I really am. There’s one hill right before Boulder, so I can’t even see where town is. The only lights ahead of me, are on a distant mesa bump, halfway between Boulder and Denver – and it never seems to get any closer. Minutes slowly grind by, as I pretend to put forth effort of riding a bike.

At last I reach the top of the final hill to the intersection of Broadway and Highway 36 that makes my “finish line” for this little challenge of mine. I’m not excited at all to finish, I just want to get home and eat something and home is still miles away and those miles seem tortuously long. The longer I try to go without food, water or sleep, the slower everything around me seems. I’ve truly have entered a new dimension.

I’m playing, and this is a game, but it’s not very much fun. Before heading home, I stop at a supermarket I never knew existed and grab a Gatorade, a Red Bull and a Coke. I can only see in fuzzy patches, and the small talk the cashier is making with me is nonsensical. He tells me about an online survey about the store I can fill out to win money and I just want to point to the Northwest and tell him, “I made it!”, but I don’t want the security guard to throw me out.

I realize I forgot to even lock my bike up outside and find myself in need to exit as quickly as possible. I get outside (bike’s still there), down the Gatorade/Red Bull, and make the last few miles home. I strip down, shower, and fix myself those half dozen eggs, strips of bacon, and corn tortillas. I feel my raw face, sunburnt from the all day exposure, and I guffaw at the gaunt image in the mirror, several pounds lighter than 20 hours ago when I left.

“God damn”, I thought, “This is all going to hurt tomorrow.”