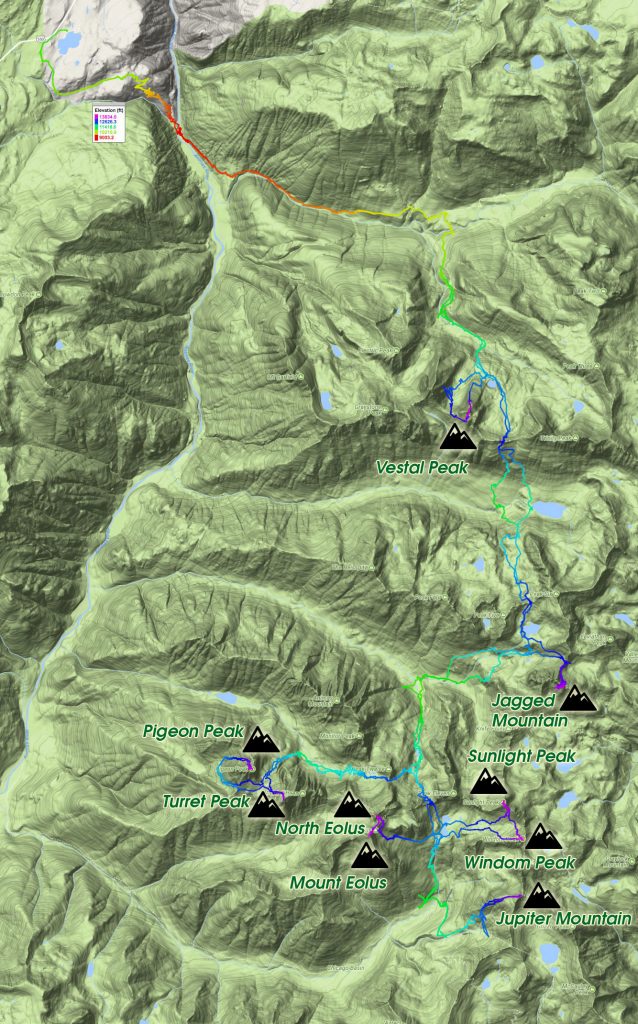

Stats (approx.):

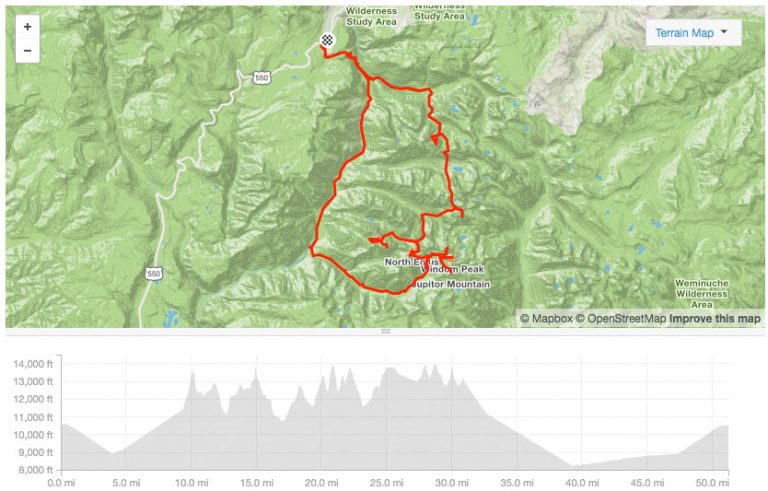

- 81.4 Miles

- 34,847’+ elevation

Total time:

- 5 days, 1hr, 44min

Nine Centennials Summited:

- Pigeon Peak

- Turret Peak

- Jupiter Mountain

- Windom Peak

- Sunlight Peak

- North Eolus

- Mount Eolus

- Jagged Mountain

- Vestal Peak

The Weminuche. This was the make-or-break section of my tour. A large project within an enormous project. Lots of terrain to cover, lots of mountains to top. Technical scrambling in a desolate setting. For example, Jagged Mountain’s easiest route rated at 5.2 is one of the technical cruxes of the whole trip and is located more than a dozen miles from any trailhead. Jagged is also one of the more remote peaks in the Highest Hundred itinerary. I also planned to take Vestal’s Wham Ridge (5.4) to summit, rather than the easier, if much looser, Southeast Couloir. I would have to descend the Southeast Couloir anyways, but Wham Ridge seemed too incredible to pass off in the name of speed.

Let’s talk logistics of even getting in there. There are nine peaks of the the Weminuche (sans the isolated Rio Grande Pyramid, which I did in a separate trip). First the good news. Five of the them: Jupiter, Windom, Sunlight, North Eolus, and Eolus are clumped into one area, easily accessible from each other in the quite popular (for Weminuche standards) Chicago Basin.

Now the bad: Turret/Pigeon, Jagged Mountain, and Vestal Peak are spaced quite far away from each other, separated by gnarly mountain passes, with no trail connecting them together.

Further complicating matters is the weather: it can be terrible, especially in the monsoon season, which is when I inevitably hit the area. With the trip being a multi-day affair and my goal of moving quickly, I could only afford bringing just so much food in my 35 liter pack, which limits how long I can stay out for. Margin of error is low, or I would face the problem of needing to go back into town to resupply, and making yet another unplanned backpack approach in, which I imagine would feel completely demoralizing for someone like me going for clock time.

For Seekers of the Self-Powered Way, there are only a few access points that make sense to gain these summits. The Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad is often used to cut down time/distance to access many of these peaks. For me, that would be of course: off the table.

One access point is the Purgatory Flats Trailhead, which I used during my Tour 14er. From Silverton, it’s a 22 mile highway ride south over two mountain passes. You’ll gain 2,625 ft of elevation and lose 3,176 ft in total. Then of course, you’ll have to re-climb those 3,176 feet back to Silverton to continue on your way west towards the Wilsons. It’s appealing to think the Durango is just a few more miles down the road, but a stop at Durango just doesn’t lead to any other mountains in my list.

Purgatory Flats itself is a ~10 mile hike/bike to the Needleton stop of the D&S, and from there, it’s yet another 12 miles into the Chicago Basin. I’d wager it’s < 6,000′ of elevation gain, with far less elevation loss. It’s a haul, but it’s all on fairly well maintained trails.

Another access point is further north, and much closer to Silverton (cutting out ride time): the Colorado Trail access from Molas Lake, only 6 miles from Silverton. You gain 1,300 feet and lose almost nothing – it sits almost at the top of Molas Pass. Sounds much more enticing, but getting to that group of Chicago Basin Centennials is still quite a bit of effort, done all on foot. Surprisingly, the mileage is pretty much the same to Twin Thumbs Pass which is right above Twin Lakes/Chicago Basin as it is from Purgatory, but the elevation gain (8200’+) and loss (6800’+) is much more extreme – and that’s not counting actually summiting any peaks along the way – that’s all extra mileage and elevation.

Although you will start on the Colorado Trail, the first thing you will do from Molas Lake is drop down into the Animas River on a never-ending set of switchbacks, only to climb up again into Elk Park valley, then into Vestal Basin. Here the trail becomes a little less than ideal, until it vanishes altogether at the base of Vestal Peak. From here until Twin Lakes in the Chicago Basin, the rest of the route is cross country.

Looking at a map, my first idea was to access the area via the Colorado Trail at Molas Lake and summit the Centennials from North to South, starting with Vestal, then Jagged, Pigeon/Turret, and finally the Chicago Basin Cents. Once finished, it made sense to follow the Chicago Basin Trail west following Needleton Creek to the Needleton train stop, then follow the trail that parallels the D&S tracks north, until I again intersected the Colorado Trail up to Molas Lake, making a large clockwise route, sweeping up the peaks as I went, and ending in an easy, if unending slog back to the bike. This would save me a ton of time and energy contending with all that off-trail hiking between Vestal and the Chicago Basin. Something a little like this:

Big problem though, and that’s: there isn’t a trail that parallels the train tracks north towards Silverton! You could theoretically follow the tracks themselves, but I was questioning if that would follow the rules and ethics that I set for myself on my self-supported, self-powered, and Fastest Known Time attempt – namely: don’t break the law/don’t trespass on private property. The tracks themselves are the railroad’s private right of way through public land. Railroads take this pretty seriously – even the boundaries of the Weminuche Wilderness are cut by the railroad’s own private right of way. The railroad is pretty clear on this, as is illustrated by this sign you’ll pass, while on the Colorado Trail, near the Animas River:

I could see justifying simply crossing the tracks to get from one side of them to the other to access an area or whatever – everyone that hikes the Colorado Trail needs to at the Animas River. But from Needleton, it’s over 8 miles back to the Colorado Trail that one must essentially trespass and 6 miles more should you decide to follow the train tracks all the way starting/ending in Silverton. That seemed a little over and above what I was willing to do to set an example on how others should go about this trip.

Crap.

My revised plan was to make the entire trip an out-and-back. A ludicrous idea, and not done all that often. No one in their right mind would access the Chicago Basin via the Molas Lake TH of the Colorado Trail, and it takes a special sense of mission to summit the other peaks on my list. But, that’s the bucket I found myself in. After the Sierra Blanca Group, the Crestones Group, The San Luis Group… I should have been used to this by now.

But still: the legitimate fastpack in would be twice as long as any other multi-day fastpack I would have done, or would be doing on this trip. Was I ready?

A worse mental state I couldn’t have possible been in, once I finally had stumbled into Silverton. I had just finished off a pretty exhausting group of peaks between Lake City and Silverton: Jones, Half, Handies, Redcloud, Sunshine, UN 13,819, UN 13,832. A good three days, but the last day featured getting stuck up high in a particularly violent thunderstorm that came out of nowhere, as well as severely denting my bike’s front rim going Mach 3 down Cinnamon Pass, trying to make it into town before it closed up for the night, as I was completely out of food. I was 5 minutes late in getting back, having burned up time throwing in a inner tube in the middle of the leveled out talus pile that passes as a road in those part. I spent the night in an uncomfortable bivy on a slice of BLM land on the side of the road a few hundred meters from town, waiting for morning to come, listening to the traffic not far away, hoping headlights didn’t reach me.

I wanted to check myself into one of more colorful hostels in the country, re-sort my gear, figure out what the hell to do about my front rim that was seriously compromised, shop for gear I had recently lost, and dodge the impending monsoon storm that was in the forecast. Maybe get some coffee while I was at it.

I couldn’t actually believe how terrible the weather had been – daily forecasts were calling for 1/4″, 1/2″ – even a full inch of rain to fall daily. Nonsensical numbers. I looked into this massive Weminuche trip I had planned out, and thought: no way, it can’t be done in such terrible conditions. Unlike the last few mountains I had summited, the Weminuche featured some of the hardest climbing of the entire trip. Something that I was looking forward to immensely, but if the routes I have chosen were wet, they would be out of condition and too dangerous to do alone. There’s no easy alt. to the top of Jagged Mountain. You’re not hiking out of the Wem. with a broken ankle.

If I couldn’t do the Weminuche – and it was looking pretty f’ing clear that I couldn’t, I would have to call the entire trip off. With less than 30 peaks summited, I wasn’t even a third finished with the trip!

I can’t say I was ever in the most perfect frame of mind to take this type of trip on from the start – I’m moody, and my mood was in a trough. If you suffer from depression, it’s not something easily shaken off, although I do my absolute best to fight it off. Bad weather, broken bike, impossible trip – it’s a pretty perfect negative feedback loop. I stewed in the hostel’s back… I dunno what to call it: barn? area where the cheapest digs were found. Heavy rain made music on the corrugated metal roof, adding a soundtrack to my melancholia.

I had one card up my sleeve, and that was to go summit Vermilion Peak right outside of town, before committing to the Weminuche. I did so with little excitement, completing the entire hike in a drizzle, with little to no visibility among tourists that were lulled into the area for it’s incredible views they also could no see. I rode back to Silverton deflated as ever.

Somehow I talked myself into at least trying the trip. I wagered that I had to at least give it one chance, and well anyways, Silverton was probably the worst possible place to scratch, as I had to somehow get out of Silverton and back home – and there’s really nowhere in on my route farther from my house than Silverton. My front wheel was holding up well-enough – it hadn’t exploded on me at high speeds, and the trip up to Molas Lake wouldn’t be dangerous to take on. Getting down would be another story, but… details, details.

The only thing really left for me to do was gather food. Silverton is most likely one of the worst places to resupply in my entire trip, perhaps outside of Fort Garland. Everything is crazy expensive, and the selection is abysmal. I scraped up what I could.

My rations included a 3lb bag of granola, two jars of peanut butter, a jar of frosting, a jar of coconut oil, a squeeze bottle of jelly, a dozen or so tortillas, a package of raisins, a half-used box of evaporated milk. I also had a few niceties: three Red Bulls, a block of cheese, and some things scrounged from the bottom of the hiker box including a whole bag of Soylent Green, and a few tossed out bags of unlabeled dehydrated food that could be eaten as a last resort.

I planned to be out for about six days. I prepared six separate ziplock bags of granola, raisins and evaporated milk. Each bag would be basically my breakfast and lunch. If I wanted to, I could mix some water to make the evaporated milk… non-evaporated, and spoon it into my mouth right out of the bag. At the end of the day, and once I had my bivy set up and tarp above me, I would give myself free access to make peanut butter/frosting/jelly/coconut oil burritos until I passed out. I don’t particularly like peanut butter, but it’s caloric density is second to none and would be where pretty much all the protein in my diet was sourced from.

With a pack full of food, I slowly rode up to Molas Lake. Six days is a long time to ditch a bike, and I still had concern over what I was going to do about that. I was having amazing luck with friendly camp hosts that would allow me to lock it near their sites to keep an eye on, and hopefully I could conjur up that magic again.

Of course though, it was night before I even reached the camp near Molas Lake, and I felt strangely not OK with just locking the bike up out of the way with just a note or something, so I decided to bivy near the trail, and find the camp host in the morning. Even though I really, really, really wanted to get moving on into my fastpack – especially since it wasn’t raining at that very second, I had to get this one detail ironed out, or all I would be thinking about is, “will my bike be there, if/when I get back”.

So, I waited till morning. The camp host appeared, was perfectly OK with me leaving my bike, although not quite so much understanding the depth of my plan. I told him to wait six days before sending in the cavalry, and I walked from the camp host cabin into the Wem. The day was looking good, and I made OK time hiking down the switchbacks to the Animas River with a heavy pack that held nothing but that 6 days of food, my sleep system, my clothes, and a few batteries/electronics.

I crossed the Animas and left one of the Redbulls down there – along with a little bit of my more undesirable food cached under a rock, knowing it was a gamble to think it would be there on my return. Once on the other side of the Animas, the trail again climbs up into the Elk Valley.

Finding the turnoff for the Vestal Basin proved easy – the area is a popular camping spot for those thru-hiking the Colorado Trail. Weather was changing a bit – getting cloudy, but I couldn’t do anything but keep moving forward. With any luck, I could climb Vestal via Wham, before calling it a day.

As I hiked on the quickly deteriorating trail, I made mental notes (as well as way points in my GPS) of possible camp sites if I found the need for them on my way back There’s just so much flat, cleared ground in the area. I noted one such patch of land, and started hiking farther up the trail, Within a minute, the sky opened up and it started to hail. In haste, I ran back to the spot and started putting up my tarp while also being covered underneath it. The weather didn’t relent, so I just took a early nap for a few hours.

Packing up again, I soldiered forward. The terrain was now waterlogged, and the well-watered foliage was now soaking me just passing by, or when I often slipped and fell from badly negotiating the tricky terrain. A miserable experience, through a through. I quickly reached another campsite, and chatted with a few climbers how had just come back from the Vestal/The Trinities earlier that day. Confirmed my thoughts on where the trail goes from there, and hiked up around the waterfall towards Vestal Peak proper.

Reaching Vestal Peak, it was obvious that the peak and route were too wet to climb safely from the storm that had only recently stopped. It seemed too early for me to stop for the day. I made the decision to skip Vestal to not waste time with an early bivvy. It was risky, as it meant I most definitely had to summit it on my return trip, and the weather could realistically be no better – or even worse, as it was right then. My other option was to wait until morning and see if the I had a dry route, but at the cost of around 12 hours of waiting. I kept going, but felt as if my trip was already unraveling using up the insurance of my out-and-back strategy, rather than shoring up some peaks.

Another invisible crux to this trip are the mountain passes. Unfortunately, not all my path follows valley floors, and getting out of Vestal Basin means crossing over a pass I’ve got little beta on, and into yet another basin. A few passes remain until even glimpsing the Chicago Basin.

The pass between Vestal and Trinity went, and in the waning light I descended into the basin (Tenmile Basin?) beyond, setting up a bivy for an early morning start on top of a boulder – the only cleared, level surface I could find that wasn’t covered in deadfall. Certainly one of the more difficult passes of my trip, and there’s difficulty not cliffing out afterwards. To think, I’ll have to re-climb this coming up!

The next morning, I continued south out of the basin, into an upper basin and crested a pass between Peak 5 and Peak 6. There’s an alpine lake on the other side, and good views of Jagged Pass, which you may use to gain entry to the east side of Jagged Mountain and the start of its standard route. I don’t remember why – perhaps the time of day, or the weather?, but I decided to skip Jagged and continue into upper No Name Basin on my way to the Chicago Basin. I may have been feeling stressed about with even getting far into my trip that I wanted to bee-line almost all the way to the farthest point, before coming back this ways. Still, the decision to skip yet another peak led to more stress and a feeling that I wasn’t completely all in on this trip. This very much isn’t like me…

From Upper No Name Basin, I followed No Name Creek to another high basin. Lucky for me, the other side of the basin south was the Chicago Basin, and my final destination. The weather was looking bad and drops of rain were already falling and I decided to stop again. When would I have a window to summit? It was somewhat early in the day, but I took a few hours nap to think things through.

Once awoke, it seemed pointless to stay here. Two choices: Continue to Chicago Basin, or go west and try to summit Pigeon and Turret. I wasn’t really game on breaking down camp and hucking my entire heavy pack up and over yet another pass – I knew I wouldn’t be fast enough to make it back to this high basin before morning, but I may be fast enough if I bring just the essentials. West sounded good, but time was tight.

I packed quickly for Upper Ruby Basin, trying not to think of what surprises awaiting for me in terms of terrain. From just below Twin Thumbs Pass, you still need to summit the pass to the west, descend into the basin, ascend another basin to a pass between Pigeon and Turret, descend a thousand feet west of Pigeon to yet again ascend up east on Pigeon’s standard route, then reverse it. It cannot be understated just how ridiculous of a route this is, although I hear that anything more “direct” is even more crazy. Turret from the pass between the two peaks is a much easier affair.

I finished up both parks by nightfall, and made my way back to my camp in the dark. Like before, on my way to Pigeon/Turret, I scoped out possible places to take an unscheduled bivy – mostly under boulders, as I had no real camping gear with me. Rain was a always a threat.

I made my way down the talus filled gully, across the wide – and wet, basin, up the glacier smooth rocks to the pass and back on the other side to my bivy. Surprisingly, nothing in my camp was disturbed, although I was sure a goat, marmot or other creature would have eaten all my food, stolen my trekking poles, and left me shipwrecked. Two of nine peaks down, and maybe my luck was turning?

Sleep that night was incredible. Being all alone, sleeping in a tiny shelter at 12,000 feet enclosed on three of four sides by sheer walls of granite – no signs of anyone else in the world – stars up above, tired body, a belly full of what could pass as food: this is what I came for.

The next day, I awoke to figure out Twin Thumbs Pass, and enter into the Chicago Basin. With enough luck, I could grab five more peaks before day’s end. Twin Thumbs acts as a threshold between the desolate, and much rarely visited part of the Weminuche and one of the most visited parts. Surmounting the pass with a heavy pack isn’t the easiest, and loose rock abounds. Even at the summit of the pass itself, you could tell the area was bustling with people. I hadn’t seen anyone else in more than a day, perhaps it will be nice to say, “hello!”?

I quickly made my way down to Twin Lakes, then down the Chicago Basin trail. Stashing my stuff high in a tree and hopefully away from hungry goat mouths, I took the fork towards the Columbine Pass Trail and then the turnoff to Jupiter’s route marked by a large cairn.

Although early, the weather was already deteriorating, so I didn’t dawdle. Much of this route is exposed, and not a great place to be stuck in a lightning and hail storm. Unfortunately for me, by the time I had reached the summit, I was definitely in one, having previewed the storm tearing up the valley my way. On the descent, I took refuge in a nook in the ridgeline, and waited out the hail as it fell.

Once I felt things were safe enough, I continued on my way down back to my gear cache. I repacked some food and hiked back up to the Chicago Basin to grab Windom, Sunlight, North Eolus, and Eolus. Windom was first, and the thunder and some rain started yet again. I decided to risk it, and just keep going for the summit, confident I’d be able to find a nook again if I needed one.

My gamble paid off, and the weather was clear enough to allow me to continue. From Windom, I took the shortcut gully to Sunlight for a quick nip at the summit, then down its standard route and across the lakes to North Eolus/Eolus. I remember these being easier peaks, but I found quite a bit of Class 3 and 4 scrambling. Shoddy memory!

I summited Elous in the middle of the night, underneith a large moon, with shooting stars hitting all over the place. Of course, I was the only one on the mountain – a theme I had replayed five times just today!

Exhausted, I made my way yet again down the Chicago Basin trail to where camping is allowed and passed out without putting the tarp up, all but guaranteeing I’d be rained on (which I was). Getting going in the morning was a chore, and I knowing the difficulty of the terrain I would need to re-hike didn’t help my motivation. I must have confused a few hikers as I hiked not towards one of the peaks in the area, but back up Twin Thumbs pass to the other side.

After a wild bushwhack back through the heart of the Wem., I made up back up to Upper No Name Basin, and there, I called it for the day. It again seemed too late to go for the summit of Jagged, although the weather was holding. I was in shambles from the past three days of effort, and just wanted to sleep. The North Face of Jagged Mountain and Grey Needle seemed to burst into flames as the sun began to wane. Again I was alone with myself and a small pack of gear to withstand the elements around me. I rested nervously, hoping that the weather would hold for tomorrow morning’s summit bid. From my camp, it’s impossible to preview the route, as the meat of it is on the other side of Jagged Pass.

An honest alpine start in the morning, and I was breaking down camp, to haul everything to the top of Jagged Pass. After a hopefully successful summit, I could leave from the pass, directly towards Vestal, and save me a little time, distance and elevation loss. Jagged Pass looked like a difficult pass to summit, but it went just fine.

After the pass, the route up Jagged Mountain takes you across a long traverse almost to a still snow-filled couloir, then up a dirty gully. I found the first pitch to certainly be a challenging one solo. Wet. I searched around for perhaps alternatives, but only found dead ends and loose rock, so I scrambled back into the gully to try again. Found the right footing, and away I went.

Jagged Mountain’s standard route is quite strange, as it’s a mixture of short pitches, ledges covered in kitty litter, and sloping grassy patches. The climbing though, when you hit it, is really good. Fun movement in a sensational setting. Being without a rope and solo, I studied each mini crux, found a solution I liked, practiced it a few times both up and down, then launched forward to the next one. Probably overkill, but I wanted to make sure I wasn’t going to get myself stuck on the descent. I hate to give too much beta away on the climb, but if you’re a lover of scrambling and vertical movement, you’ll love Jagged Mountain.

Within little time, I had gained the ridge, and had wrapped around the other side. A nice exposed traverse and a fantastic chimney got me onto the quite incredible summit. A perfect day: sunny, still, crisp, and cool.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have too much time to dawdle, and had to keep this train going. From the summit of Jagged, Vestal Peak is easily spotted, but so is the labyrinth path back to Vestal Pass. The descent down Jagged went smoothly – the scrambling is all incredible, and since I worked on the moves so much, my movement was fluid. Even the last pitch down to the traverse back to Jagged Pass didn’t seem so head scratching. I must have had psyched myself out earlier – or maybe I wasn’t quite woken up, yet.

I picked up the rest of my cached gear, ate a snack, watched a search and rescue copter fly around the basin to the east looking for who knows what, and then made my exit. The route back to Vestal Basin is somewhat complicated, and completely off trail and thus, slow. Alpine scenes like this one do not help with quick flight:

I felt quite refreshed from the previous day’s extended sleep sess., my pack was now dangerous light from lack of food, and as the crow flies, it’s only 3 1/4 miles from Jagged Pass to the base of Vestal Peak’s Wham Ridge route. Still, it took me 6 1/2 hours to get there on the trackeless and challenging terrain.

By the time I got to Vestal Lake, it was 4:00pm. The weather again was disintegrating, and I had to make a call on if I should go for the summit now, and make yet another early bivvy. I felt pretty stoked from Jagged Mountain, so I took a micro nap to wait out the dark, heavy clouds circulating above me, decided to throw caution to the wind, and then started up this monster:

And just like that, I couldn’t really feel the last four days in my legs – the fatigue seemed to melt away, as a smile formed across my face, and began to climb upwards. The climbing felt so familiar to me, having done so much scrambling on Boulder’s Flatirons since I moved there in 2014. But Vestal Peak was stupendously oversized when compared to any of the Flatirons which makes one also feel so small. Looking up from the base, Vestal Peak’s Wham Ridge slowly curves up to near vertical, as its sides taper together, forming a small summit.

I joyfully paddled up the holds as the route got steeper and steeper; more and more difficult. I realized at that moment that my depression seemed to also be lifting and with a little more luck, I was well on my way on completing what I thought to be just a few days ago: impossible.

A few hundred feet above me was my ninth summit for this part of my tour, and I felt invincible in getting on top. It wasn’t just the difficulty of the climbing – although sometimes that helps to focus one’s energy, but everything had finally come together to allow me to glimpse a life experienced plus ultra.

A few cruxy and steep sections later, and I was on that summit. I took a small break, like I usually do, centered myself, and descended quietly. The descent route on the backside is particularly nasty, and I’m almost tempted, the next time I’m up here (because there will be a next time), to just downclimb the way I went. I decided to go west after the gully gets less pronounced and downclimb some tricky terrain between Vestal and Arrow Peak. It was questionable if it would go from atop, but it was fine enough for me. My route plopped me on top of a large and slow-going rock glacier, but I was in a fantastic mood, singing to myself and filled with energy.

I again, fetched my cached of gear, and said a somewhat sad farewell to the deep interior of the Weminuche I was now immediately leaving, the same interior I felt I would never find a way out the other side of. In a few hundred meters, I would again be on something that at least approximated a trail, and any chance of getting woefully lose were now slim. My food stores were also gettin’ slim, my plan was to hike out as far as I could, and take a few naps along the way. Took a brief snooze at the Colorado Trail junction, but felt no real reason to stop there for the night. The net elevation until the Animas River would be a loss, so fast, easy hiking was all that awaited me. A lonely hike with no one really to stop and talk to – or even see, but I guess that just helped to make good time.

At the Animas, the prospect of hiking those switchbacks up, and making so much vert back to Molas Lake didn’t seem particularly inviting, so right by the bridge, I made a pitiful bivvy to sleep off a few hours of fatigue. In the morning, I searched for my cached food, but of course when I found it, the food in every plastic bag was picked exquisitely clean by some woodland creatures. The Redbull though, was untouched. It doesn’t always make the best breakfast, but this morning, it felt somewhat perfect. So did the prospect of real food that very morning!

As if cross the threshold into another world, crossing the Animas River brought with it signs of human life and activity care of the Colorado Trail thru hikers, enjoying their own mornings by eating breakfast or playing a small musical instrument they had packed in. I must have looked a mess – but just only a little bit more than they were used to. The tininess of my pack may have confused some.

The endless switchbacks up to Molas Lake do actually end. I checked into the bustling morning of the camp host’s office, thanked them for looking after my bike, made sure that they knew I was OK, grabbed the bike, and gingerly steered it back down into Silverton on that bad wheel, towards some coffee.

The day was still incredibly early as I finished with town, so there was no need for me to stop in Silverton for the night. I slowly pedaled on towards The Wilsons after another resupply to see me through the night, the next day of tagging four more difficult peaks, and getting all the way to Telluride where Dallas Peak awaited me. I felt an intense sense of confidence in completing the rest of the tour – even though the hardest climbing was still to come. The Wemiminche I thought, was a wild ride. If I could survive the Wem. – I could survived anything!

My route, and anything similar, is much more difficult than what the mileage and vertical gain/loss would have you believe, even though these numbers themselves aren’t exactly low. Once off trail, you’ll encounter a variety of obstacles: large fields of willows, multi-leveled basins connected by rocky gulches where the only route up is literally hiking up a waterfall, overgrown avalanche chutes, deadfall everywhere, large pools of standing water, exposed ridgelines, and terrible, terrible weather. The many basins you’ll have to connect are not straightforward. The crux could very well be described as the approach to the peaks – especially the passes, and not the peaks themselves. In comparison to many other parts of Colorado I visited on my tour, this was surely one of the more wildest.

[…] the numbers really don’t compare to the Crestones, Sierra Blanca – let alone the mighty Weminuche. A motivated person, starting early with fine weather, could potentially do this course between […]

[…] trail runner (I would run an ultra in these, without hesitation), kicks for fastpacking – like my time in the Weminuche, and even for a scramble a low/moderate pitch of alpine rock when the great majority of the time is […]

[…] Fastpacks From Hell: The Weminuche Throwdown […]

[…] Fastpacks From Hell: The Weminuche Throwdown […]